Table of Contents

Dreams and Realities on the Home Front: Canadians’ Call for Government Action on Housing Affordability is a joint research project between the Broadbent Institute and the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Canada. The survey was conducted in the field by Viewpoints Research.

About the Author

Clement Nocos is the Director of Policy and Engagement at the Broadbent Institute.

The author would also like to thank the following for their instrumental support in this analysis.

Jordan Leichnitz, Canada Program Officer, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

Natalie Pilla, Research Associate, Viewpoints Research

About the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is the oldest political foundation in Germany with a rich tradition in social democracy dating back to its foundation in 1925. The foundation owes its formation and its mission to the political legacy of its namesake Friedrich Ebert, the first democratically elected German President. FES established a Liaison Officer in Canada in 2008, in coordination with the US FES Office in Washington DC.

Key Findings

Overall, a strong majority of respondents from both the BC Lower Mainland and the GTHA want to see the federal government get back into building housing (80%), with 41% wanting the Government of Canada to get back into building more non-market housing, and 39% looking for a “mixed” approach to let developers build more market housing with non-market housing.

Housing affordability is a concern for most respondents (81%)-it’s either a top concern (24%) or within their top five concerns (57%).

More than a third of respondents in the Lower Mainland and the GTHA (37%) say that they cannot afford their current housing situation if the cost of their monthly rent or mortgage payments increased by 10% in the next year.

Most (57%) think they are spending over 30% of their before-tax househoAAld income on their rent or mortgage and half (52%) have at some point felt at risk of losing their home or becoming housing insecure.

80% of renters hope to own their home at some point, but most think it’s unlikely (23%) or very unlikely (56%) that they could purchase a home in the next five years.

Most think that foreign investors (48%) are the most responsible for housing becoming more expensive, followed by the federal government (39%), real-estate developers (32%) and corporate landlords (31%).

More than half of respondents thought the following policies would really or might help them:

- Instructing the Bank of Canada to consider lowering interest rates (68%)

- Giving people the option of more easily moving to different lenders when they re-negotiate their mortgage (63%)

- Offering incentives to developers to build affordable, non-market rental housing (60%)

- Using government-owned land to develop affordable rental units with rent caps (57%)

Introduction

Housing has been a priority concern for Canadians, particularly those living in the most unaffordable urban centres across the country, for years before the COVID-19 pandemic led to economic shocks and inflationary pressures across the economy, sending rent and house prices sky-high. Since 2023, housing affordability has become one of the hottest political issues in Canada – as more and more Canadians struggle to find a place to call home, political parties are defining themselves around their response to this pressing issue.

Housing is a social good, like public healthcare, and is recognized as a human right in Canada under the federal government’s 2019 National Housing Strategy Act. Despite this, since major federal funding cuts in the 1990s, the federal government itself had largely divested itself from housing, contributing to today’s crisis.

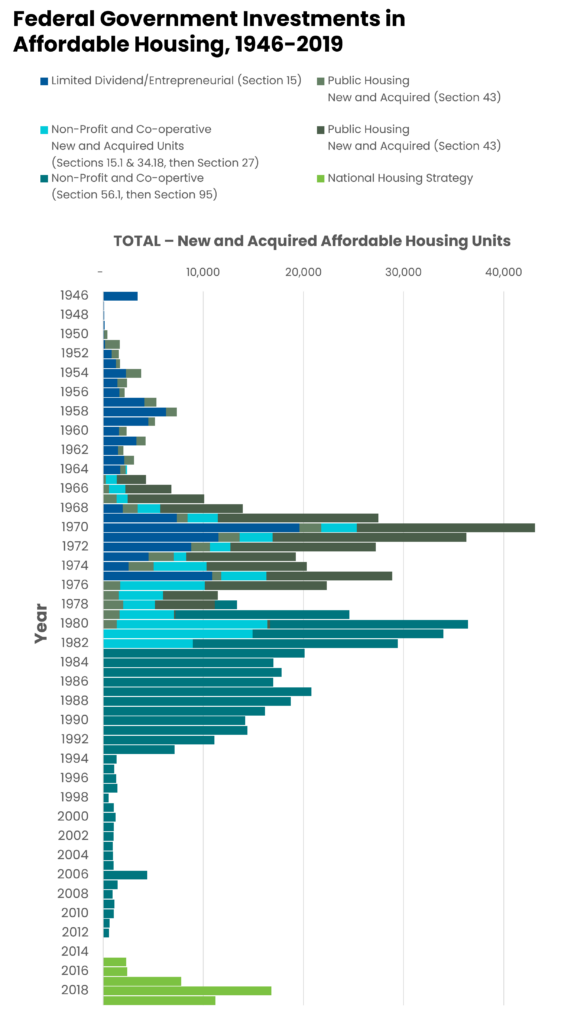

Chart 1 — The federal government has stepped away from investments in affordable housing since the 1990s, only now increasing in recent years

The disappearances over decades of public investment in affordable housing supply and the financialization of housing–where mortgages and homes are treated as assets for financial investment–are major factors contributing to the present affordability crisis.

While federal Conservative leader, and former housing minister, Pierre Poilievre claims that the government should get out of home-building as the solution to the crisis, the reality is that the federal government has already been absent for decades.

Where markets fail, it is up to governments to ensure that no one is left behind and to meet the government’s commitment to housing as a human right.

Today, housing affordability is the most pressing political issue in Canada. According to Leger’s August 2023 survey on The Housing Crisis in Canada, a clear 95% of Canadians think increasing rental costs and the lack of affordable rental homes in Canada is a serious problem.

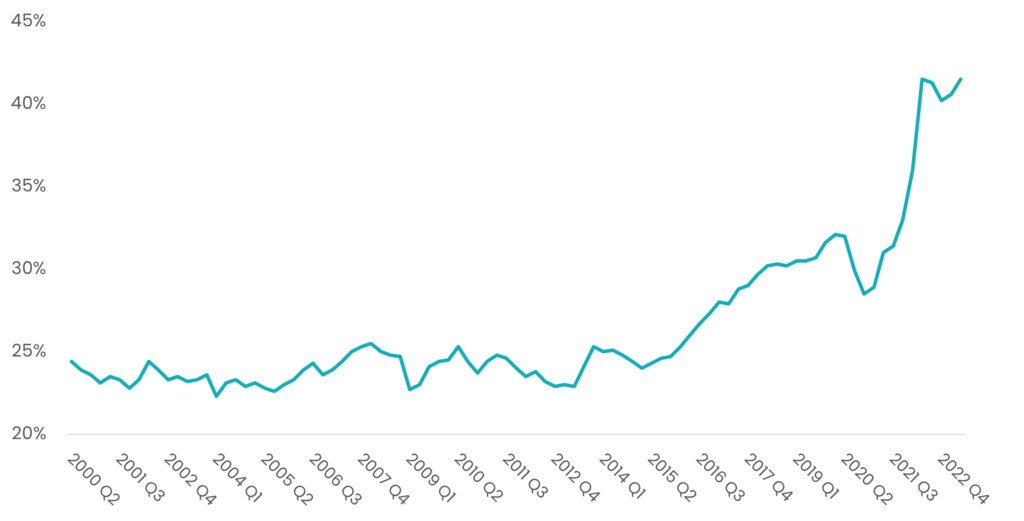

Chart 2 — In 2023, a record share of income would have been required to pay for the monthly homeownership expenses of a condominium apartment in the GTA

(median household before-tax income in the region as % of condominium market price)

In late 2023, Leger also found that 66% of Canadians surveyed think the federal government should allocate more funds to its housing strategy. According to Abacus Data in October 2023, 90% of young Canadians believe the government should prioritize ensuring housing is affordable.

It’s a stark reality that ordinary Canadians face today. According to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) January 2024 Rental Market Report, in the BC Lower Mainland region the average two-bedroom purpose built rental unit grew in rental price by 8.6% from the previous year to $2,181 while the vacancy rate was 0.9%. Vacancy rates were even lower for the most affordable units, where households already spend a greater share of their income on rent. Similar trends appear in the Greater Toronto region, where purpose-built rental market prices increased by 8.7% and housing expenses have dramatically eaten into the proportion of household income.

Governments can address this issue by “getting back into housing,” but do Canadians recognize this need and how exactly do they want government to get back into housing? In the Greater Toronto & Hamilton Area (GTHA) and BC Lower Mainland, two of the most unaffordable housing markets in the country, the government of British Columbia and the new Mayoral administration in the City of Toronto have begun bold housing initiatives over the past year, bringing in programs that lead to decommodification, increased supply, and housing protections for working-class families.

With these recent announcements, backed by federal government support to increase their impact, provincial and municipal administrations are certainly getting government back into housing. But what exactly are the current affordability pressures faced by ordinary Canadians living in the two most expensive housing regions in the country? How are people thinking about these pressures, and what are their aspirations and worries around housing? And what are the government housing policies that, in their view, are needed to relieve those pressures?

This survey looks at the BC Lower Mainland and the Greater Toronto & Hamilton Area, where housing prices have increased dramatically in the most expensive regions for housing in Canada, and where governments are looking to get back into the business of building housing and acting on affordability. It reveals key findings demonstrating the uneven effects of the housing crisis, and what policy changes are seen as needed and effective by those experiencing some of the most severe housing affordability challenges in Canada.

Methodology

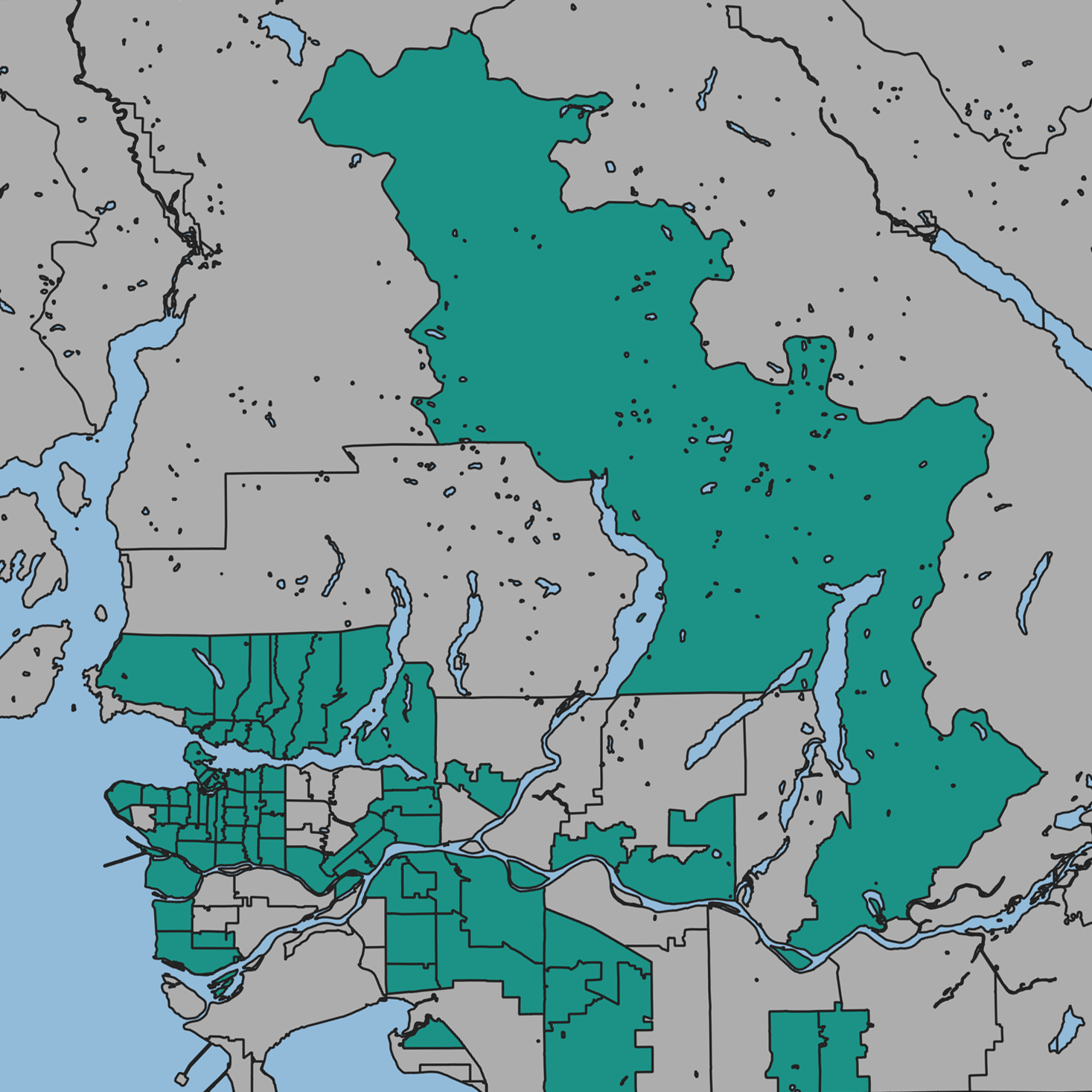

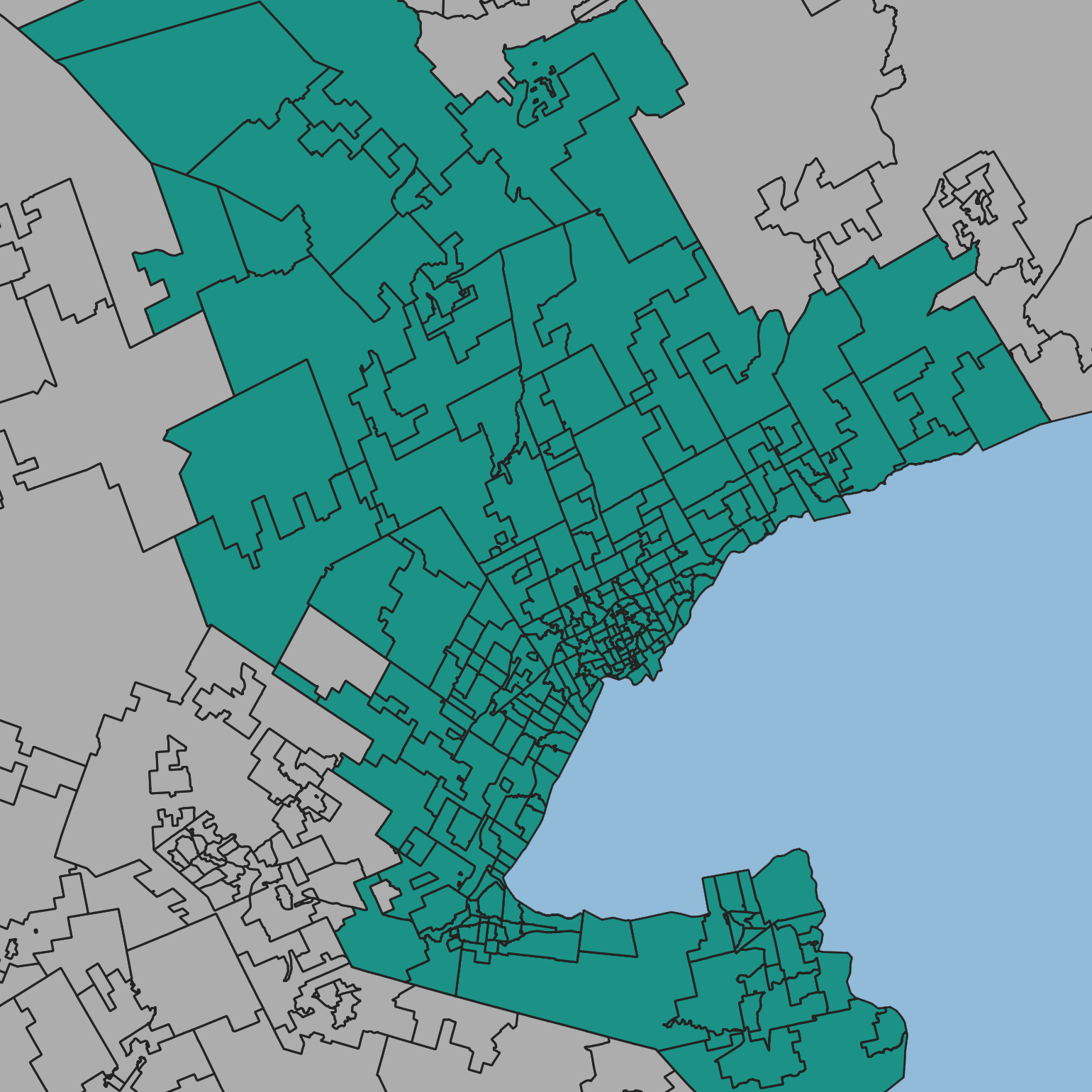

This survey was conducted by Viewpoints Research with respondents who live in the Greater Toronto & Hamilton Area (GTHA, including Barrie and Golden Horseshoe) and the BC Lower Mainland. See below for the postal code range used in this survey.

BC Lower Mainland

Greater Toronto & Hamilton Area

The survey included weighting to ensure responses reflect the actual distribution of the population by age, gender and region using Statistics Canada Census 2021 data. It was conducted online using a web survey with 617 responses participating be-tween February 14th to 26th, 2024. The margin of error for an equivalent random sample of the same size is +/- 3.95%. Numbers presented have been rounded up, and sums presented used raw figures before rounding.

Gaps in Prioritizing Housing Affordability

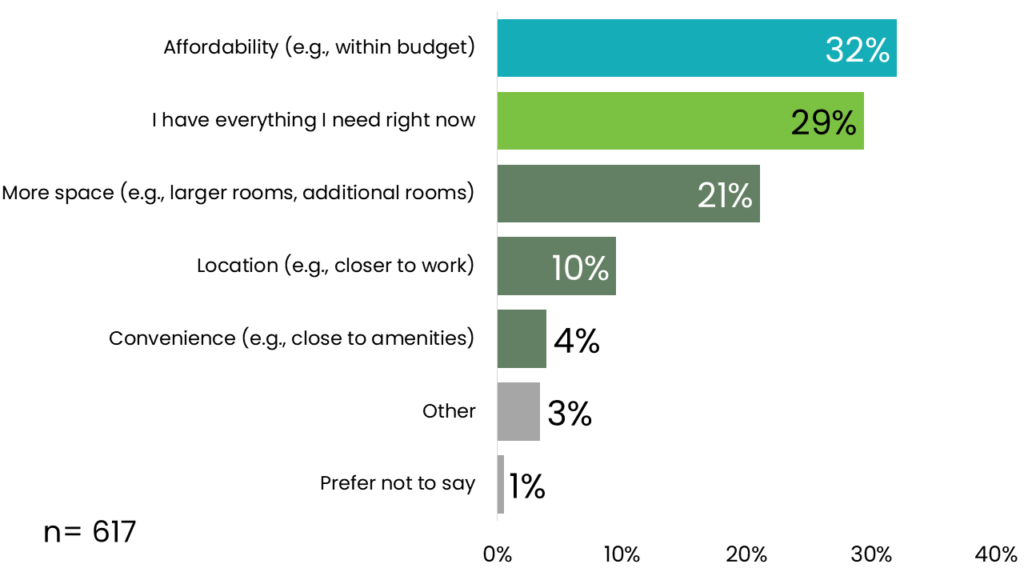

Chart 3 — When you think about what you need in a home that you don’t have right now, what do you want the most?

Amongst survey respondents, affordability (32%) is the top concern when it comes to housing, to ensure that housing costs remain proportional to household incomes and budgets. However, the desire for more space (21%), location (10%), and convenience (4%) are also aspects of housing related to cost (i.e., higher cost housing would likely achieve desires for more space, better location, and convenience). Thus, housing affordability is a high priority amongst respondents, and it greatly influences many of their other concerns.

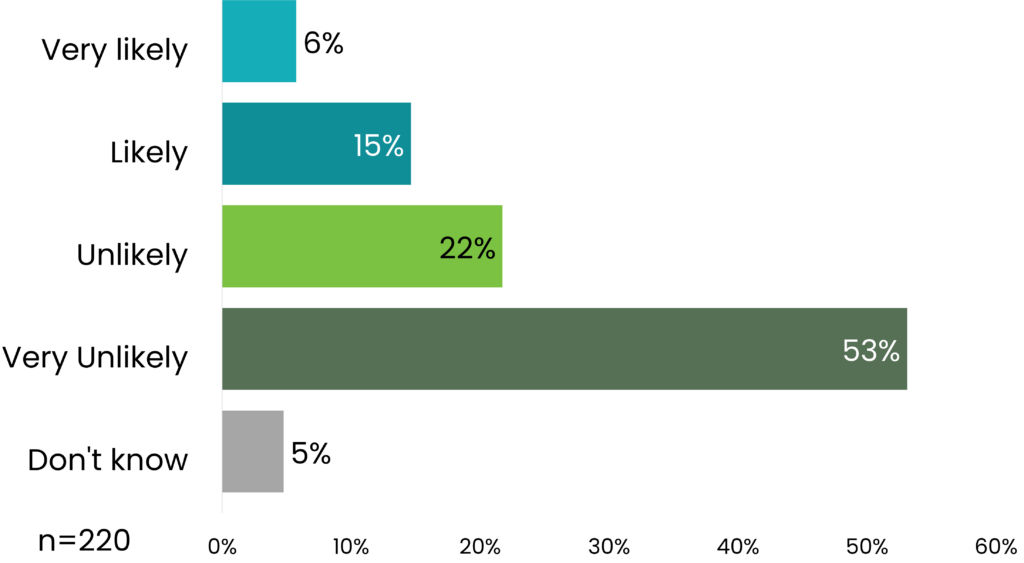

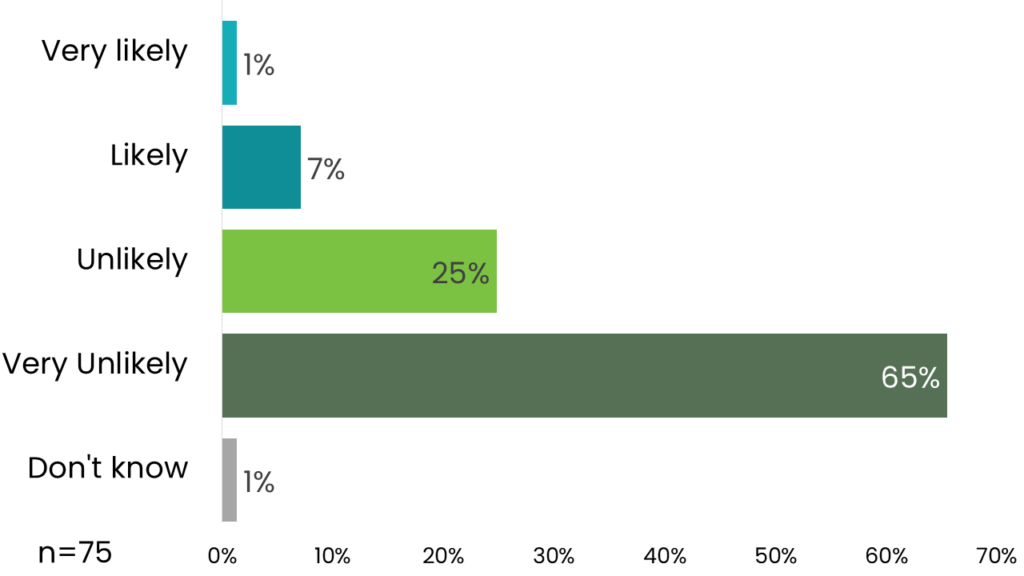

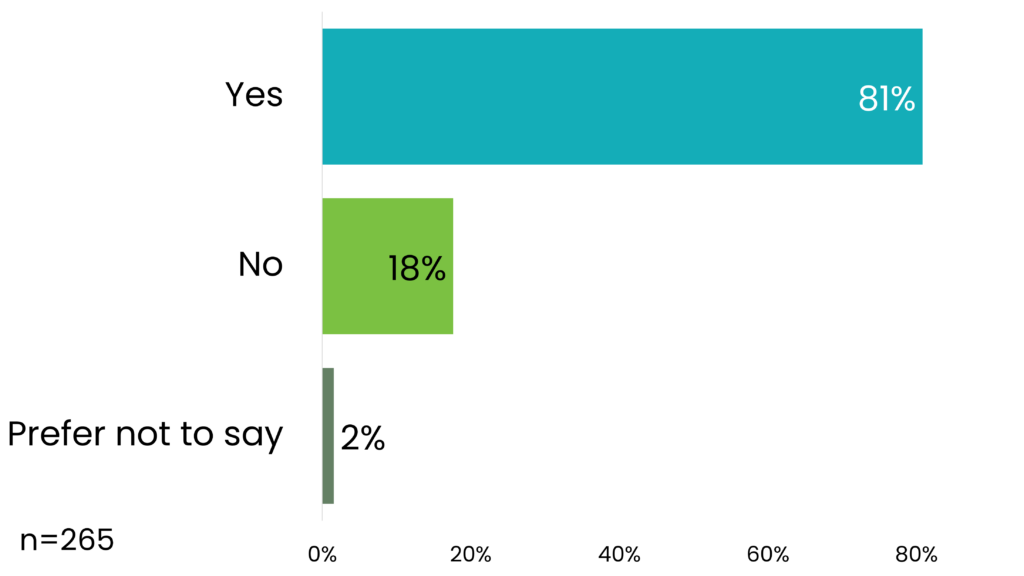

Despite the clear concern among respondents with affordability, the vast majority of renters are still holding onto the dream of home ownership. 81% of renters (see Chart 15) hope to own their own home at some point, but most think it’s unlikely (23%) or very unlikely (56%) that they could purchase a home in the next five years. Younger renters are particularly pessimistic, with 65% saying that they think it’s very unlikely that they could buy within the next 5 years.

Chart 4 — How likely do you think it is that you could purchase a home in the next five years? (non-homeowners only)

Chart 5 — How likely do you think it is that you could purchase a home in the next five years? (19-29 years old; non-homeowners only)

When people consider what’s missing from their current housing situation, most people are looking for better affordability (32%) or more space (21%). Almost half (46%) of those aged 18-29 are looking first and foremost for affordability, and for a third (30%) of parents more space tops their housing wish list.

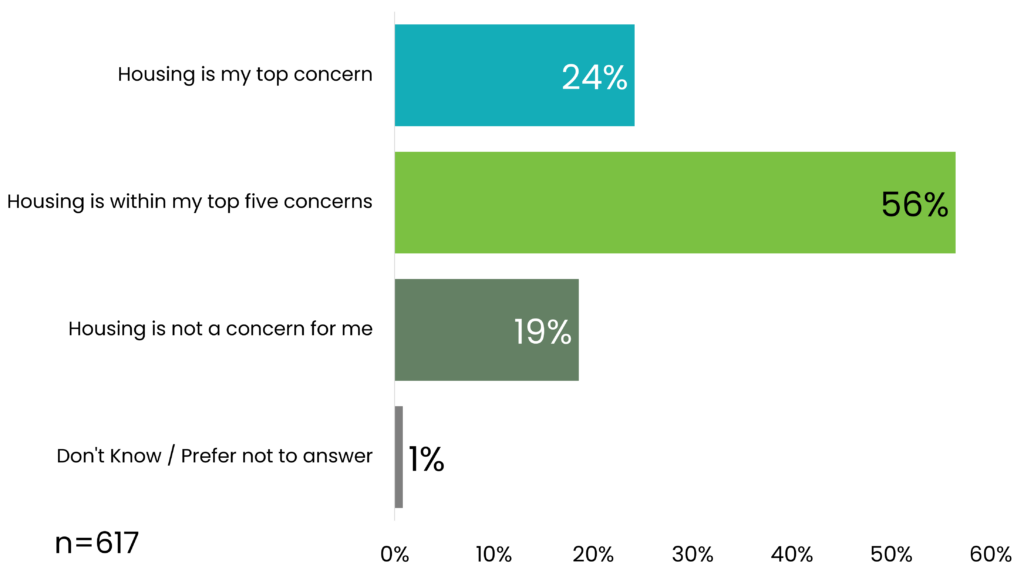

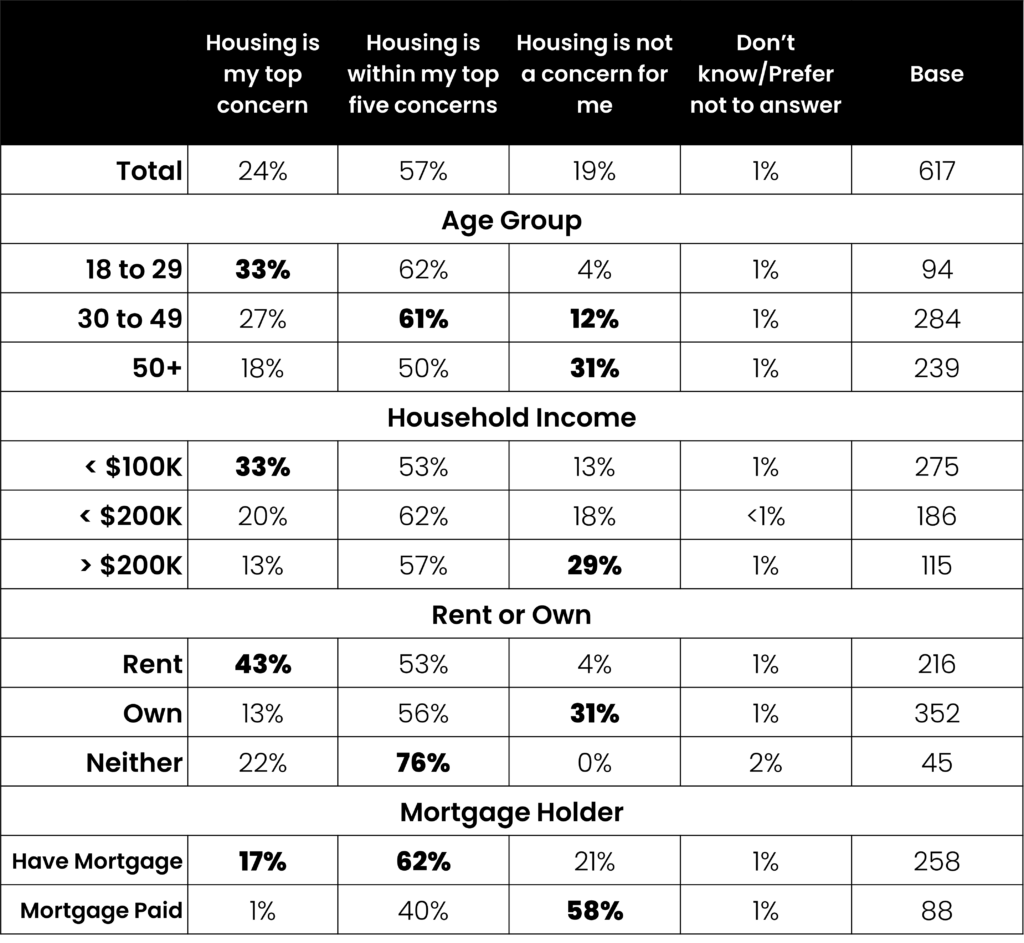

Chart 6 — Among the issues and concerns you have in your life, how high would you rate housing affordability?

Housing affordability is a concern for most respondents (81%)-it’s either a top concern (24%) or within their top five concerns (57%). With the highest housing costs in the country found in the Lower Mainland and GTHA regions, it is unsurprising that the issue is top of mind for a strong majority of respondents.

There is also a clear generational gap when it comes to who is concerned about housing affordability. 95% of respondents from the youngest age group of 18 to 29 year olds said that housing affordability is one of their top concerns (33% top concern; 62% within my top five concerns). For middle-aged respondents, 87% said that housing affordability is one of their top concerns (26% top concern; 61% within my top five concerns). While a majority of respondents aged 50 and older felt that housing affordability was one of their top concerns (18% top concern; 50% within my top five concerns), nearly a third felt that housing was not a concern for the (31%).

Notably, a large percentage of those aged 18 to 29 neither rent nor own the housing they live in (33%), implying that this substantial portion of respondents in this age group may be living with family or friends. 53% of respondents aged 18 to 29 are renters, and are the most likely amongst all age groups to be earning less than $40,000 annually. 86% of respondents whose household income is less than $100,00 a year said housing was a top concern for them (33% top concern; 53% top five concern).

These figures regarding concerns over housing affordability among 18 to 29 year old respondents contrast starkly against the older generation. Those 50 and older, who likely own their homes, are also more likely to belong to the group who have paid off their mortgage. Of those respondents who have paid off their mortgage, 1% say that housing is their top concern while 58% say that housing is not a concern.

That the pressures of the housing affordability crisis are felt unevenly across generations indicates that prescriptive policy measures to address the issue must consider the economic challenges being faced by these disparate segments of the population, notably among young people, lower-income households, and renters.

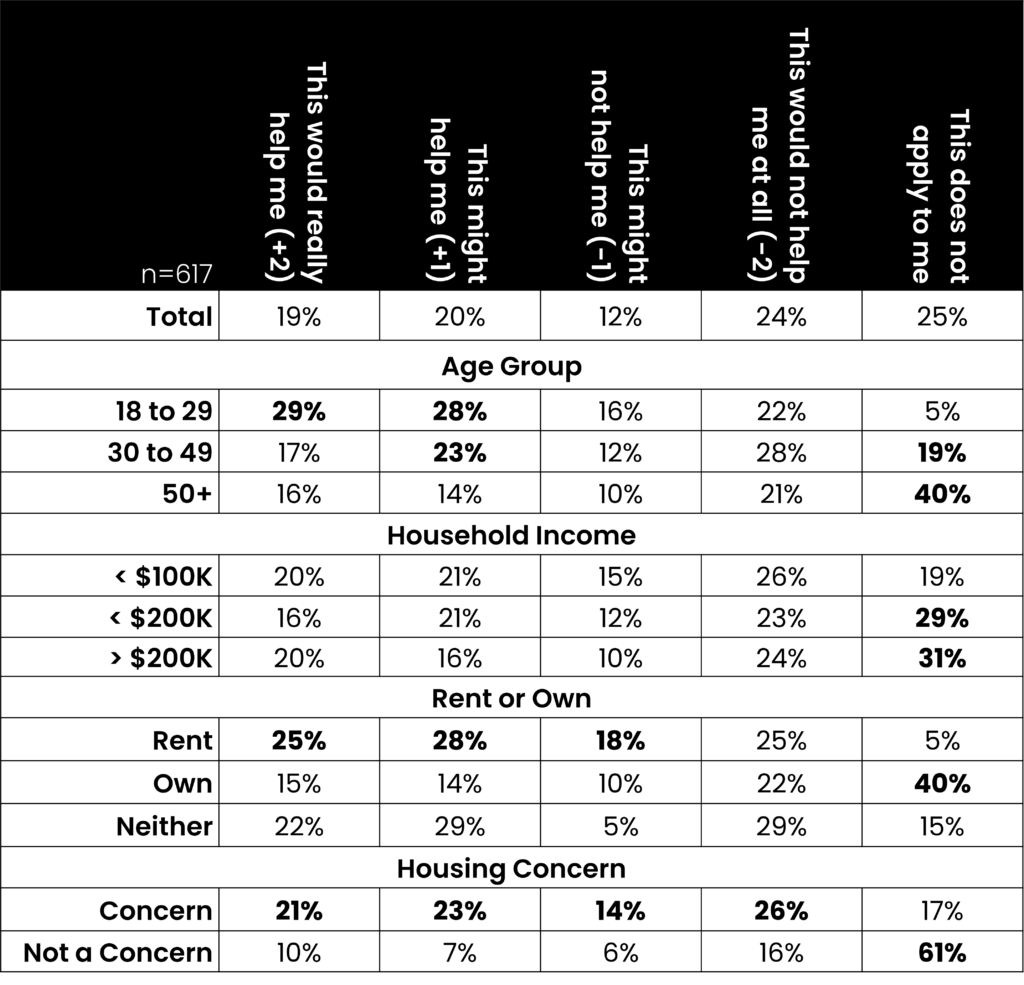

Table 1 — Among the issues and concerns you have in your life, how high would you rate housing affordability?

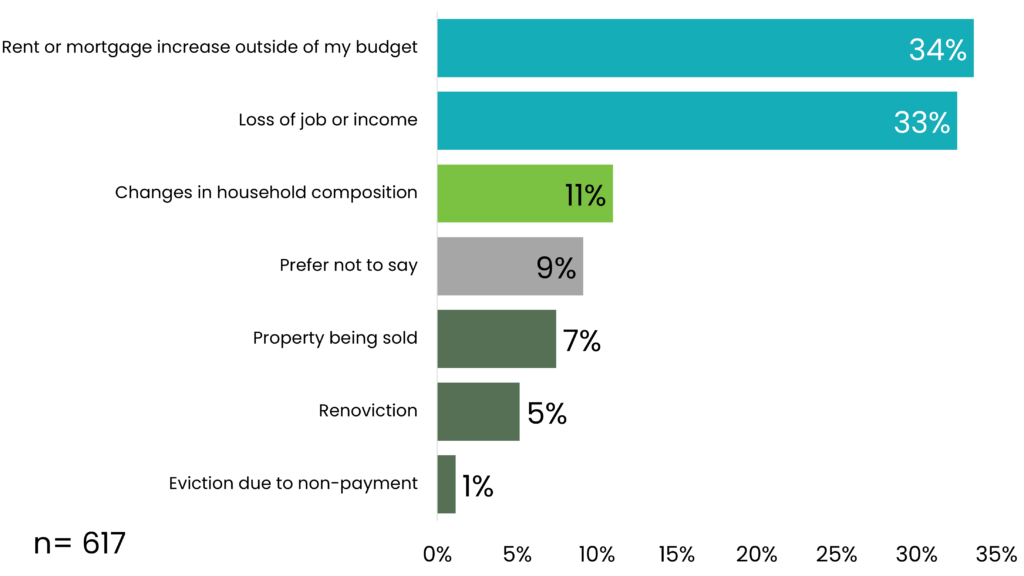

Chart 7 — When you think about the issues that might cause you to lose your home in the next year, what are you most concerned about?

Survey respondents were mostly concerned about increases in rent or mortgage (34%) and loss of their job or income (33%) when it comes to potential loss of their home. Both these concerns highlight how central affordability is to housing precarity. Housing precarity is disproportionately experienced between generations, household incomes, and whether respondents are renters or homeowners, when looking at whether they could afford an increase costs to their current housing situation.

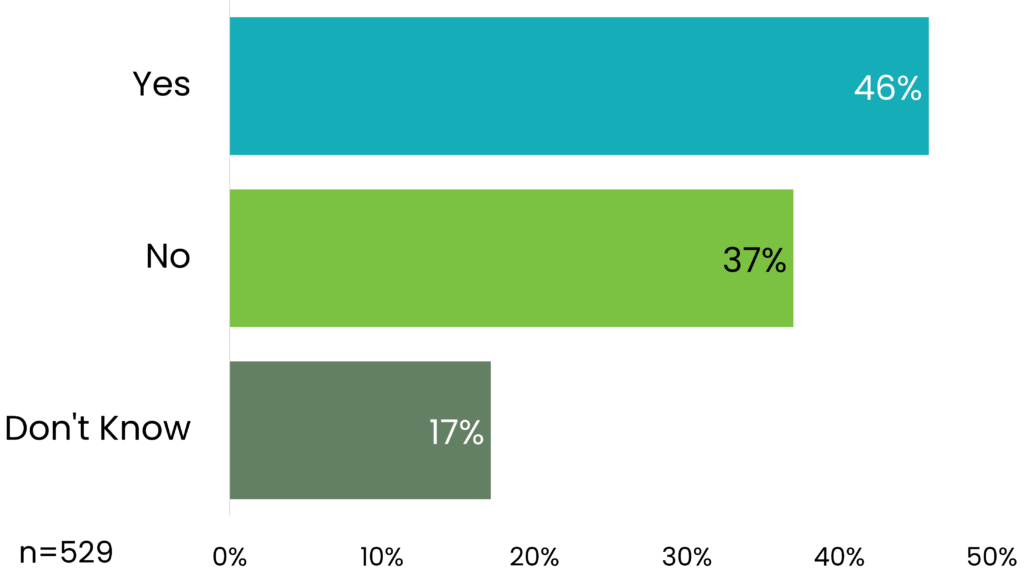

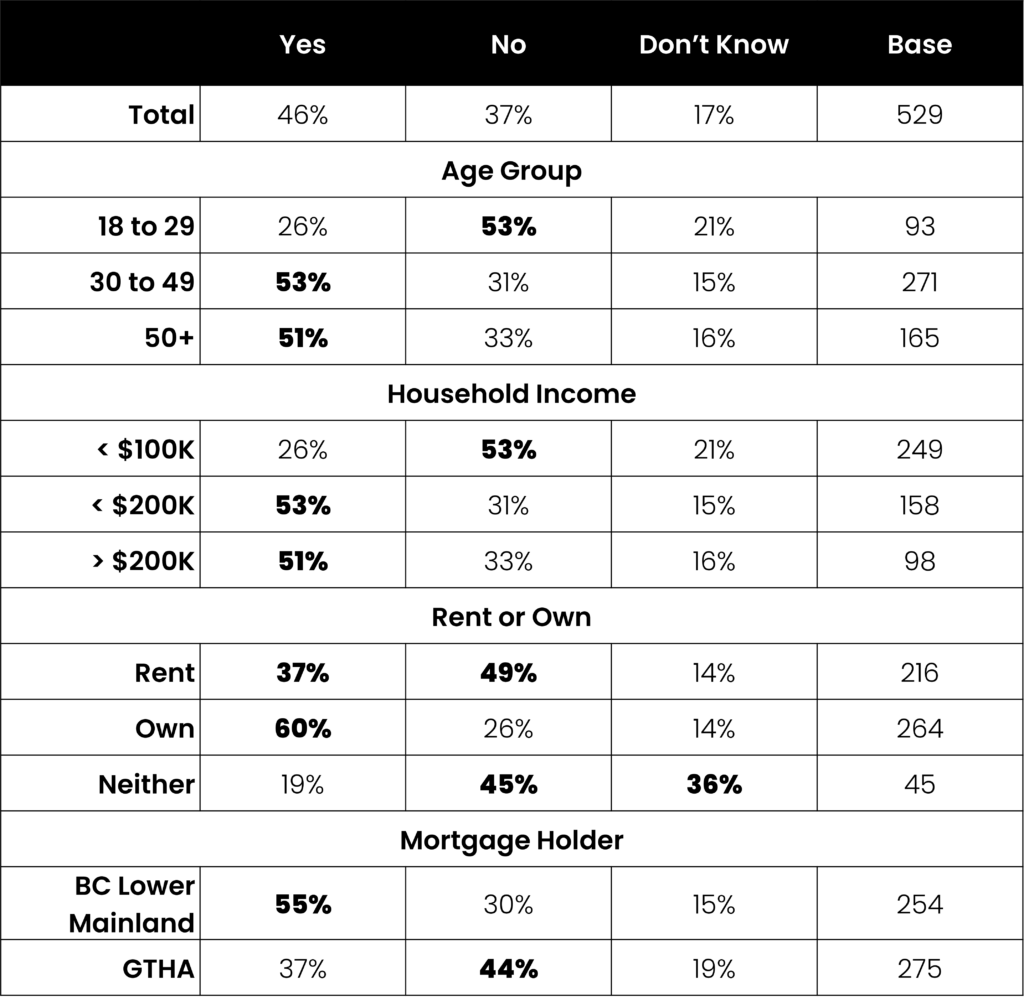

Chart 8 — If the cost of your monthly rent or mortgage payments increased by 10% in the next year, could you still afford your current housing?

Remarkably, more than a third of respondents (37%) say that they cannot afford their current housing situation if the cost of their monthly rent or mortgage payments increased by 10% in the next year. Living close to the line on housing affordability is particularly acute in the GTHA, where 44% could not afford a 10% increase in housing costs, compared to 30% in the Lower Mainland. There are also a substantial number of respondents who are unsure if they could afford a jump in their current housing costs (15% in Lower Mainland; 19% in the GTHA).

A 10% increase in housing costs would have the greatest impact on people aged 18 to 29, as only 26% of respondents in this age category feel they could afford it. Fore respondents aged 30 to 49, this rises to 53% and to 51% of those 50 and older. Unsurprisingly, 70% of those respondents with household incomes less than $100,000 cannot (50%) or are unsure (20%) whether they could afford such a jump in housing costs.

Table 2 — If the cost of your monthly rent or mortgage payments increased by 10% in the next year, could you still afford your current housing?

For those respondents with mortgages, a quarter (25%) could not afford such an increase in their mortgage costs while 15% are unsure whether they could afford the jump in prices.

Notably, nearly half of renters (49%) could not afford this increase while 14% are unsure. Among homeowners, just over a quarter (26%) could not afford a 10% increase in mortgage payments in the next year and 14% remain unsure.

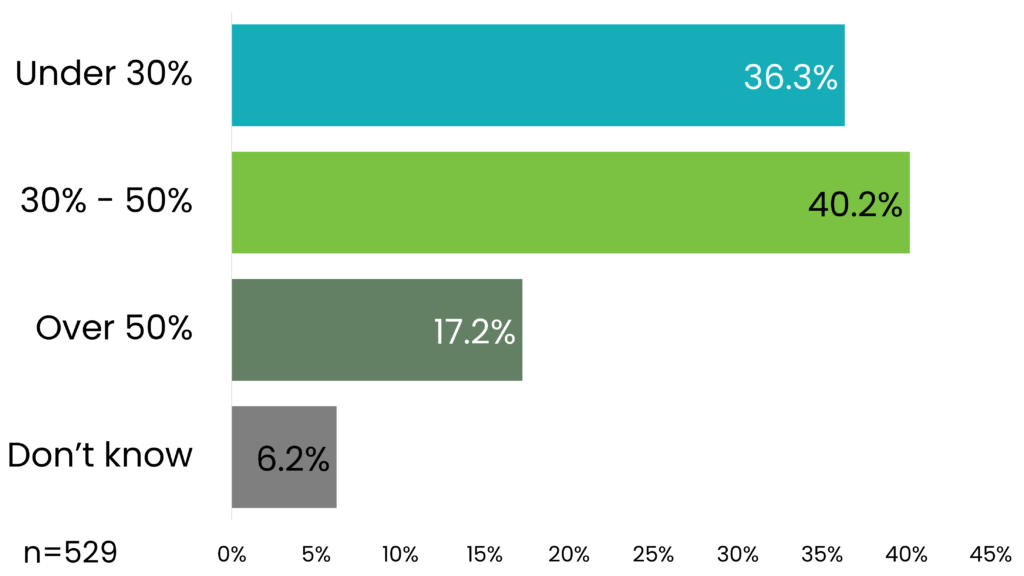

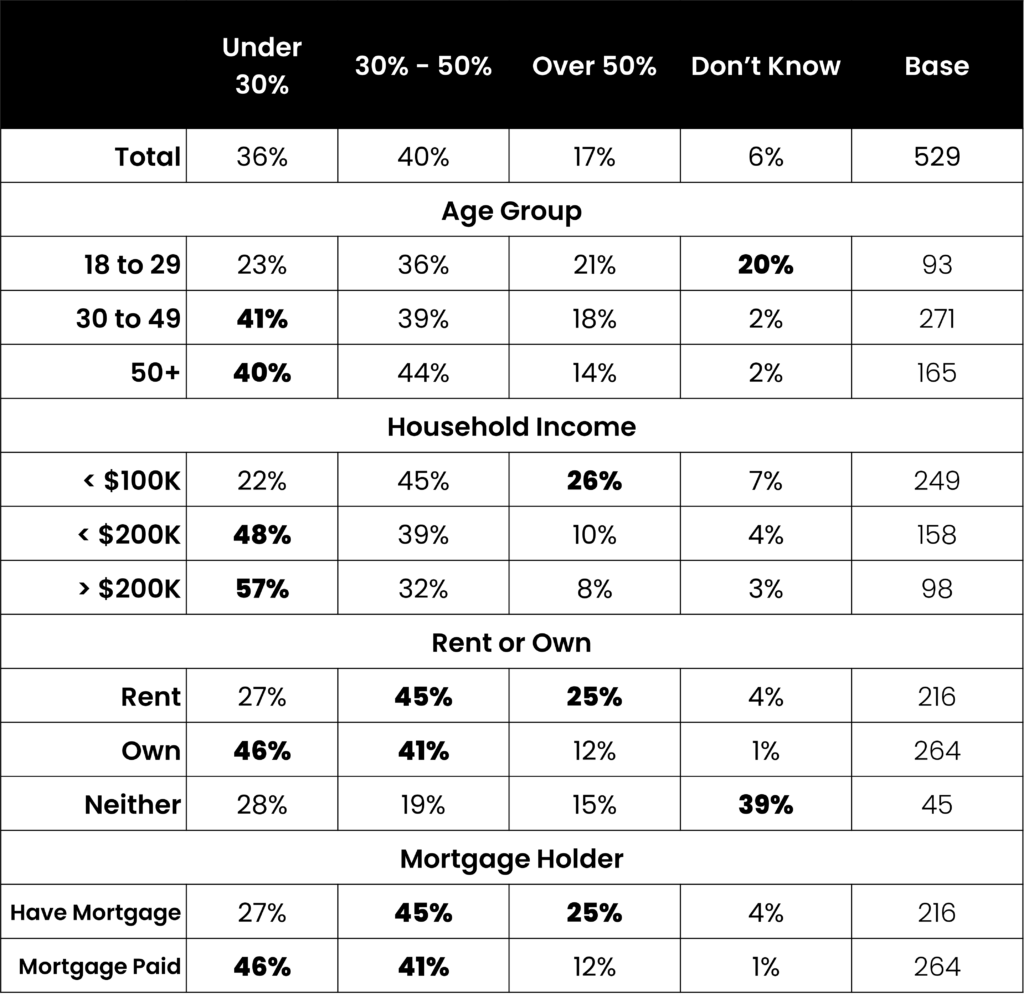

Chart 9 — What proportion of your before-tax household income do you think you spend on your rent or mortgage?

This outlook on the ability to afford a 10% increase in rent or mortgage costs can be related to the substantial proportion of respondents who reported spending more than 30% of their household incomes on housing costs. According to the CMHC, “as a general rule, your monthly housing costs should be no more than 32% of your average gross (before-tax) monthly income.” Housing costs that are higher than this take way from other household spending or savings needed for everyday life and are considered unaffordable.

Most (57%) of those surveyed report spending over 30% of their before-tax household income on their rent or mortgage. A quarter (25%) of renters are spending over 50% of their income on monthly rent payments. Combined with above average overall inflation since 2021, this contributes to the strong indication from the previous section that most (54%) respondents are unable to or unsure if they can afford a 10% increase in housing costs in the next year.

Table 3 — What proportion of your before-tax household income do you think you spend on your rent or mortgage?

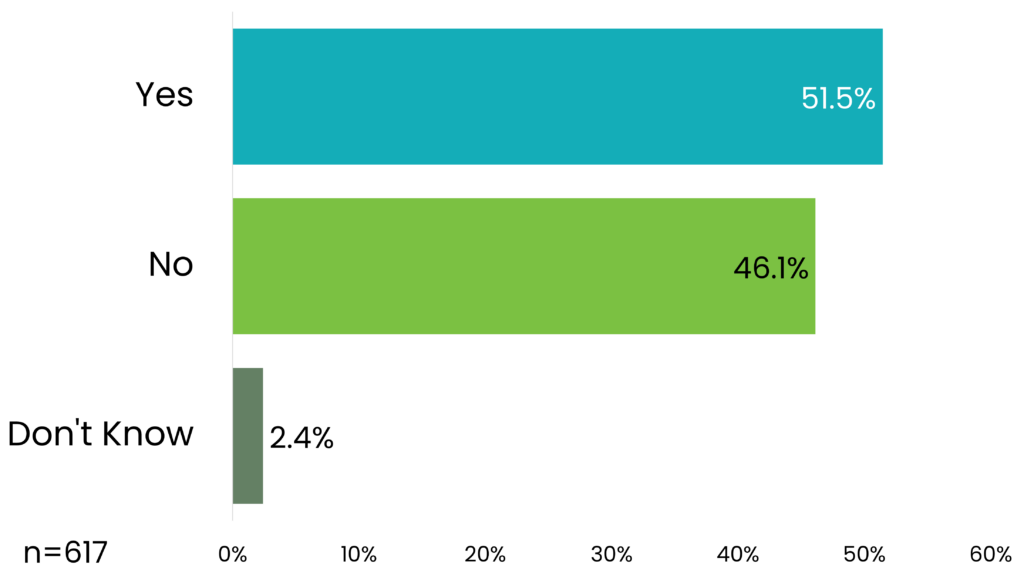

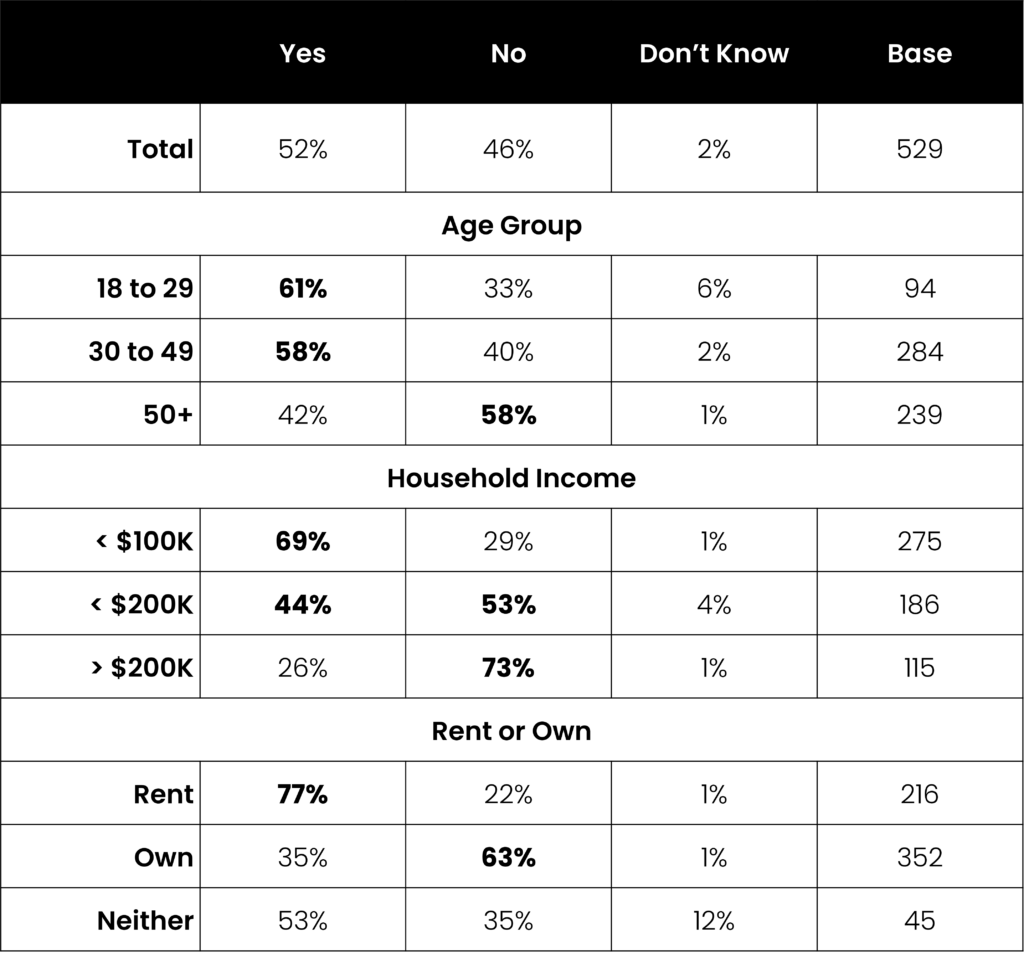

Chart 10 — Have you ever felt at risk of losing your home or becoming housing insecure?

The substantial housing precarity that survey respondents reported and the high proportion of household income reportedly being spent on housing costs contributed to the finding surprise that more than half (52%) of respondents have felt at risk of losing their home or becoming housing insecure. This feeling was especially common among those 18 to 29 years old (61%) and 30 to 49 years old (58%), those whose household income is less than $100,000 annually (69%) as well as those who rent (77%).

Table 4 — Have you ever felt at risk of losing your home or becoming housing insecure?

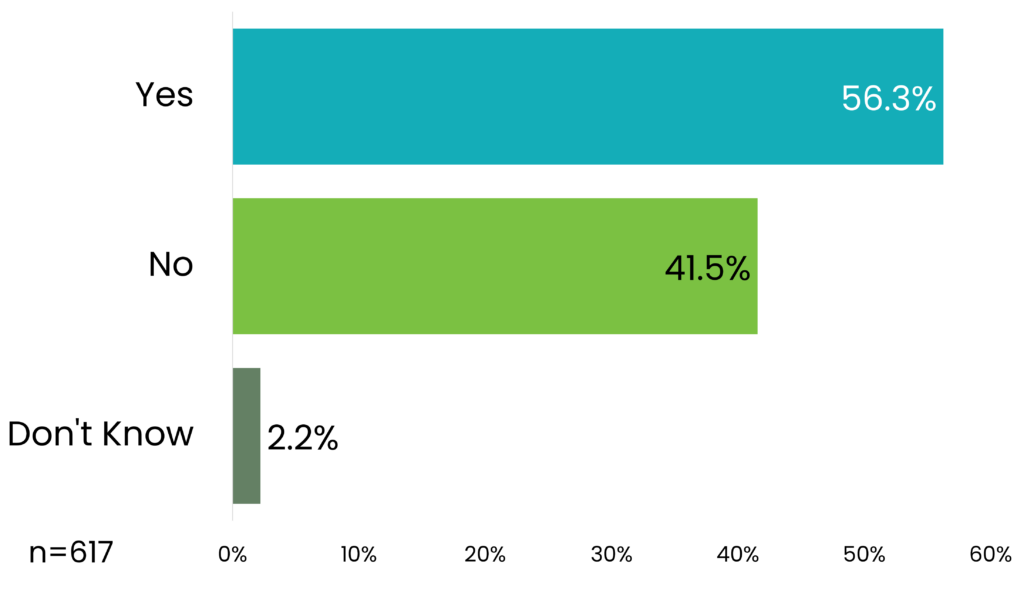

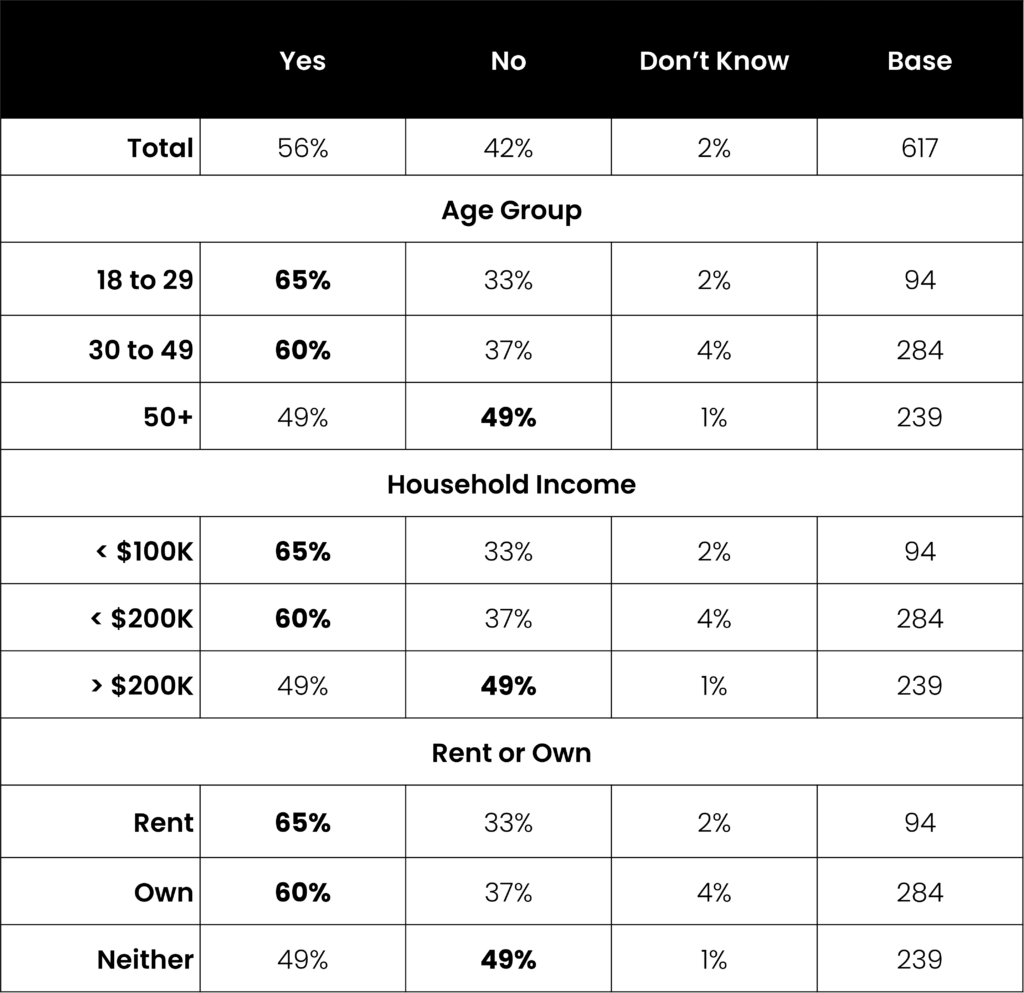

Chart 11 — Do you know someone personally who has experienced homelessness? This can include living temporarily with family or friends, living in a vehicle, living in a shelter, or experiencing street homelessness.

At the extreme end of unaffordability is the crisis and experience of being unhoused. The experience of homelessness in this regard is not just street-involved, but includes experiences with being unhoused where shelter is found with networks, shelters, vehicles, etc.

56% of survey respondents reported knowing someone personally who had experienced homelessness. Among young people 18 to 29 years old, a substantial majority (65%) know someone who has experienced homelessness, followed by 60% of 30 to 49 year olds. For those whose household income is less than $100,000 annually, 65% know of homelessness within their close social networks and nearly two-thirds (73%) of renters know of homelessness experiences in their personal lives.

Table 5 — Do you know someone personally who has experienced homelessness? This can include living temporarily with family or friends, living in a vehicle, living in a shelter, or experiencing street homelessness.

There are clearly substantial differences in the way the housing affordability crisis is experienced between younger and older generations, low-income households and higher-income households, as well as between renters and homeowners. These perspectives carry over into attitudes about who is responsible for the housing crisis, and the best ways to solve it.

Getting Government Back into Housing: Problem or Solution?

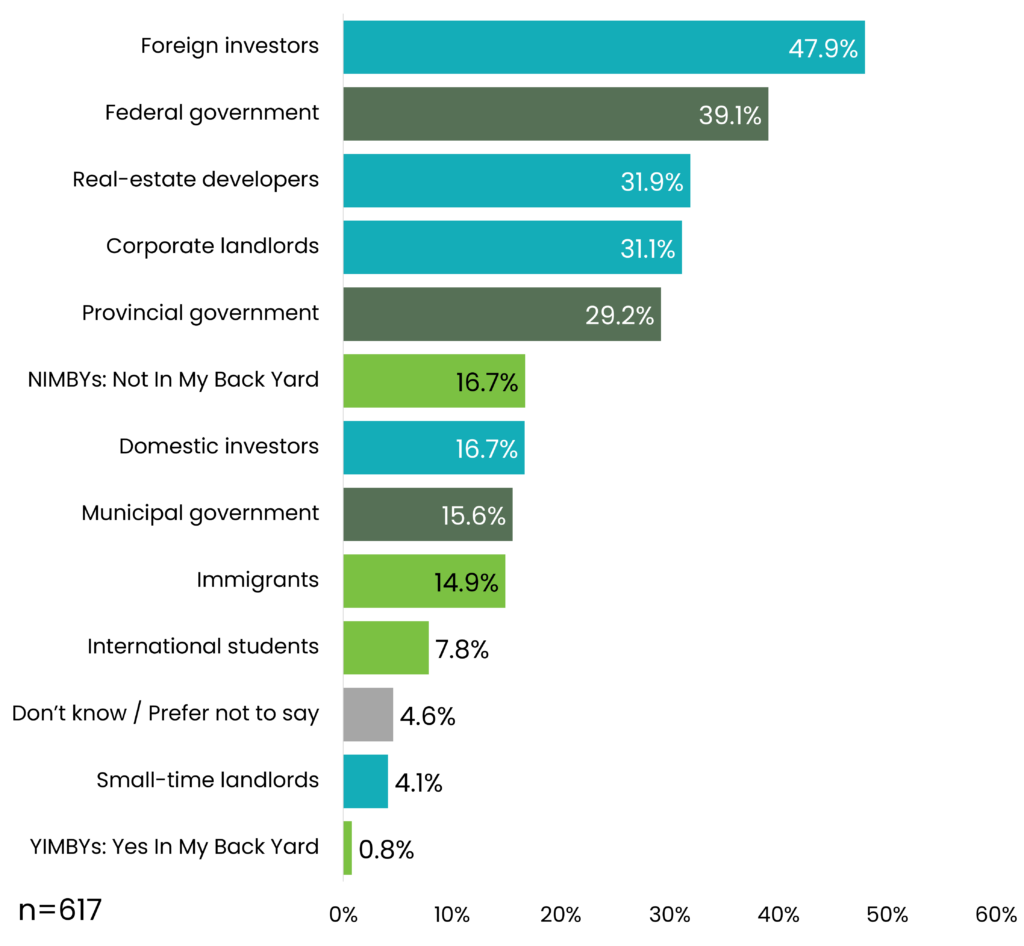

Chart 12 — Who do you think is more responsible for housing becoming more expensive? Select up to three of the options below.

When asked who, “is most responsible for housing becoming more expensive,” respondents pointed to a number of financial and government actors as culpable for the present crisis. Foreign investors (48%), real-estate developers (32%), and corporate landlords (31%) round out the top three financial actors most responsible for housing unaffordability. Government actors like the federal government (39%) and provincial government (29%) make up the remaining top five found most responsible for increasing housing costs.

These findings suggest that Canadians understand that the financialization of housing is a significant factor behind rising housing costs. It’s notable that despite the federal government’s greatly diminished role in housing in recent decades, this level of government is still viewed as most responsible for the current situation. The federal government is also not responsible for some of the administrative “interference” that are perceived to “get in the way” of housing. This finding is particularly interesting given that municipal governments are responsible for policies that directly affect housing affordability such as zoning, infrastructure, and approvals–yet only received perceived top responsibility for the crisis by 16% of respondents. Perceptions of capacity to tackle bigger issues, recognition of the smaller tax revenue base cities can generate, and varied administrations in the GTHA could account for municipal governments being held less responsible than other levels of government.

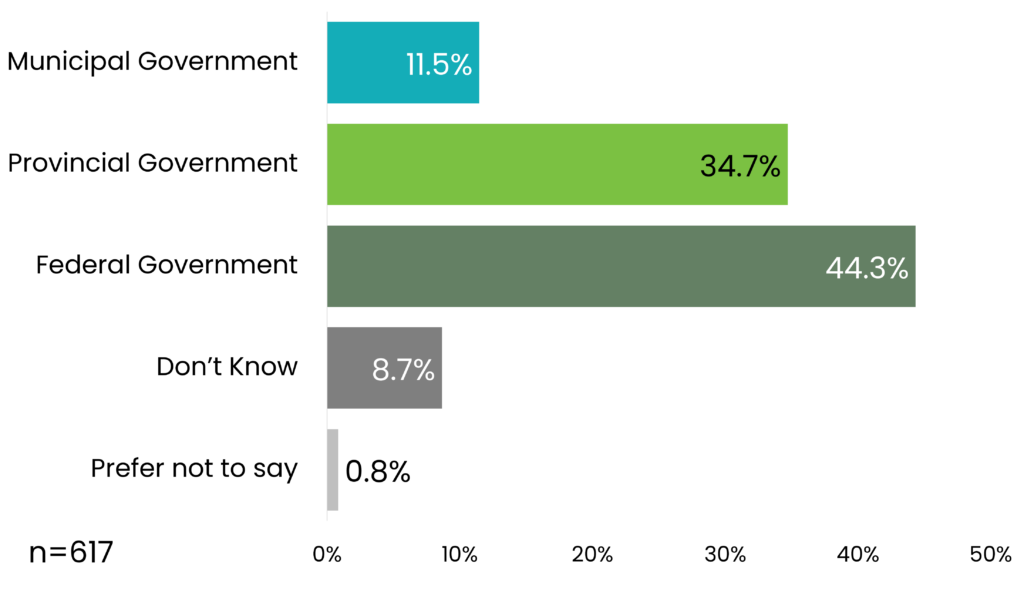

Chart 13 — Which level of government do you think is most responsible for addressing housing unaffordability?

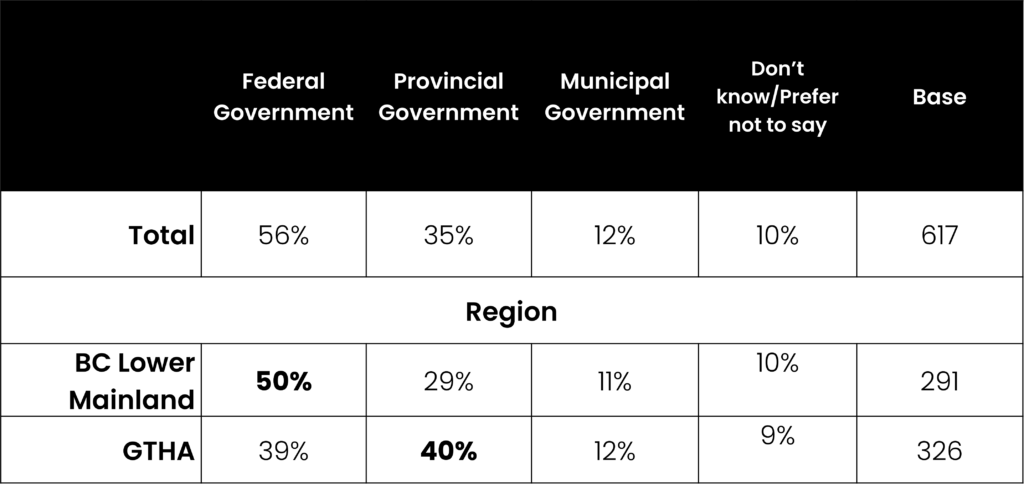

Among the different levels of government, the federal level is seen as most responsible for housing unaffordability by 44% of respondents, followed by provincial government (35%), and municipal government (11%). Notably, this outlook between which government is most responsible for the housing crisis differs between the BC Lower Mainland and the GTHA.

In the BC Lower Mainland, significantly fewer respondents blame the provincial government (29%) compared to the federal government (50%)–a finding that could be attributed to a flurry of recent housing policy announcements by the Government of BC meant to relieve affordability pressures through a combination of reforms and investments aimed at increasing housing supply at the time of the survey.

The Government of Ontario, however, has more recently been mired in scandal regarding policies that favoured real estate developers in the environmentally protected Greenbelt. As identified by respondents, real estate developers are one of the top financialized actors responsible for the housing crisis in Ontario; 32% of GTHA respondents view real estate developers as one of the most responsible actors for the housing crisis.

Given these developments at the time of the survey, respondents have assigned a higher proportion of blame (40%) for unaffordability to the provincial government. The perceived closeness between developers and the Ontario government could contribute to this negative perception. The federal government shares nearly equal blame (39%) as the Ontario government in the GTHA for housing affordability.

Table 6 — Which level of government do you think is most responsible for addressing housing unaffordability?

The differences in assigned government blame for the housing affordability crisis between BC Lower Mainland and the GTHA respondents show some indication that governments that get back into housing to push back against financialization and increasing decommodification, are seen more favourably than those that do not or are slow to act.

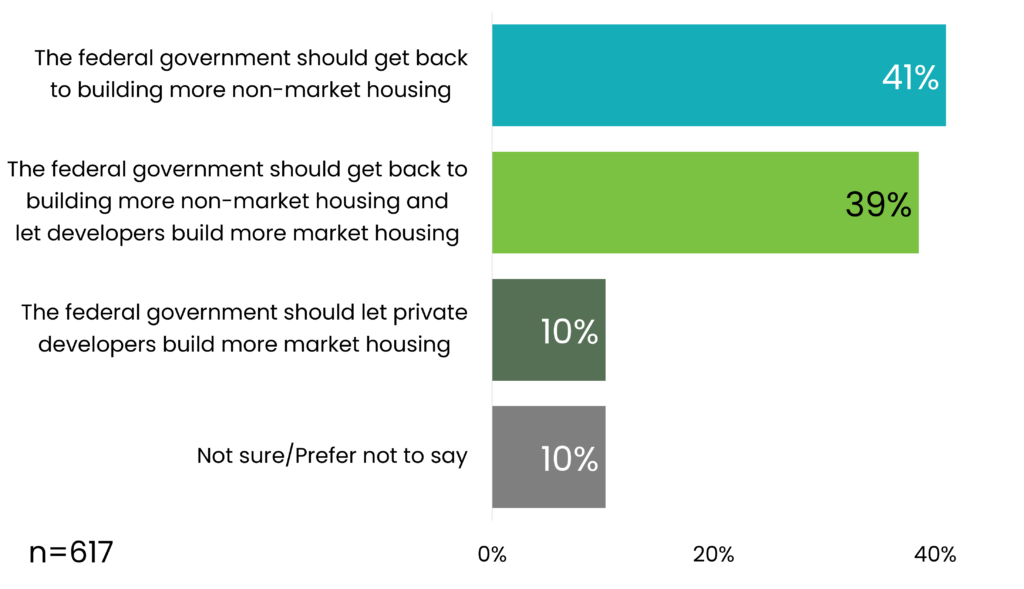

Chart 14 — From the 1940s to the 1990s, the federal government funded and built a substantial amount of non-market housing for Canadians. Their involvement has changed since then, and there’s now a shortage of market and non-market housing options for those who need it.

Non-market housing is offered at below-market rates or is tailored to people’s incomes to make them more affordable. Market housing is offered at standard prices based on supply and demand. With that in mind, please select the statement that you agree with the most.

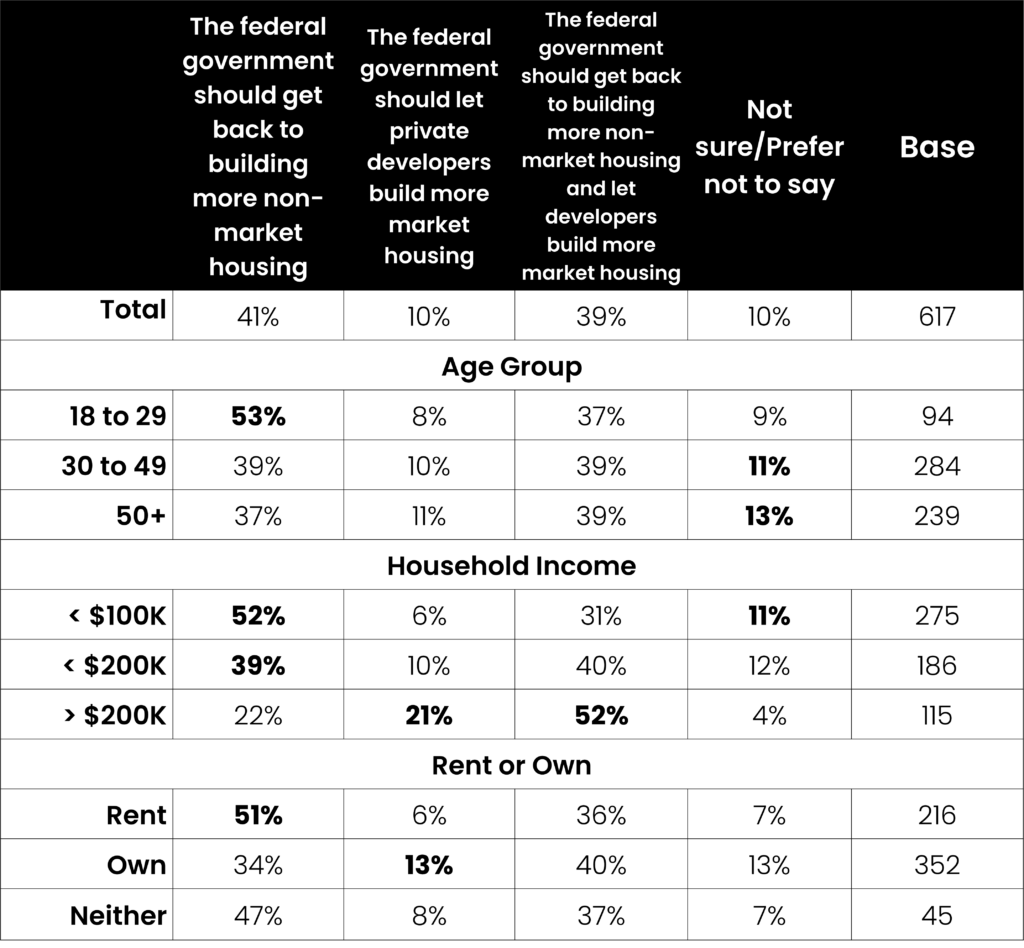

Overall, a strong majority of respondents from both the Lower Mainland and the GTHA want to see the federal government get back into building housing (80%), with 41% wanting the Government of Canada to get back into building more non-market housing, and 39% looking for a “mixed” approach to let developers build more market housing while the federal government also builds non-market housing.

Among the younger generation aged 18 to 29 years old, a majority (53%) say the federal government should get back into non-market housing, and an additional 37% want a mixed approach with government and private investment. A majority of 50-year-old and older respondents also say there is a need for government to get back into housing (37% government non-market, 39% mixed).

For respondents whose household incomes are less than $100,000 annually, 52% want to see the federal government back in non-market housing, and 31% prefer a mixed approach. Similarly, a majority (87%) of renters want to see the federal government back in housing, with 51% looking for a non-market housing approach, and 36% want the government back in a mixed approach. Notably, among homeowners, 74% want to see the government get back into housing, with 47% preferring the non-market housing approach and 37% desiring a mixed-market approach.

Table 7 — From the 1940s to the 1990s, the federal government funded and built a substantial amount of non-market housing for Canadians. Their involvement has changed since then, and there’s now a shortage of market and non-market housing options for those who need it.

Non-market housing is offered at below-market rates or is tailored to people’s incomes to make them more affordable. Market housing is offered at standard prices based on supply and demand. With that in mind, please select the statement that you agree with the most.

Despite identifying the federal government as one of the most responsible actors for the housing affordability crisis, respondents overwhelmingly want the federal government to get back into building housing. The need for government involvement in addressing the housing crisis is clear, and a deeper look at policy preferences shows just how survey respondents want governments to act on the housing crisis.

How Should Governments Get Back into Housing?

In this study, rather than asking which policy interventions people support in theory, respondents were asked whether they believed that policy proposals would actually help them personally address housing affordability challenges.

Policy responses that “would really help me” or “might help me”, according to respondents, are notably geared towards homeownership and building more nonmarket rental housing supply, a finding that likely reflects the continued hope that many have for home ownership despite financial challenges (81%) and policy preferences that could help home ownership aspirations.

Chart 15 — Housing affordability aside, do you hope to own your own home at some point?

Instructing the Bank of Canada to consider lowering interest rates is perceived as the most helpful intervention (68%) by respondents. Giving people the option of more easily moving to different lenders when they re-negotiate their mortgages would be helpful to 63% of respondents.

Regarding decommodified housing supply, 61% believe that offering incentives to developers to build affordable, non-market rental housing to be helpful. More than half (57%) of respondents would find using government-owned land to develop affordable rental units with rent caps as a helpful housing policy initiative.

Significantly, policies that respondents indicated “might not help me” or “would not help me at all” include those regarding taxes. Respondents found a more progressive property tax to be the most unhelpful (58%) of the policies surveyed. Eliminating capital gains exemptions for principal residences (52%) and “cutting the carbon tax” (50%) were also found to be unhelpful policies for housing affordability.

Table 8 — Below are some housing policies that have been proposed or implemented. Thinking about what would improve your personal housing situation, please select how helpful each policy would be.

How Governments Can Help Renters

A number of policies directed at helping renters are significantly correlated with renters themselves. However, appearing in the marginals in Table 8, the sentiments towards pro-renter policies are not as strongly supported when homeowner preferences are included. Among renters, policies such as rent control (92%), using government-owned land to develop affordable rental units with rent caps (87%), offering incentives to build affordable, non-market rental housing (85%), rent geared-to-income (76%), vacancy control (70%), limited or shared equity ownership (66%), offering incentives to build more market rental housing (65%) are well-supported.

Still, linked to aspirations to homeownership among renters, the idea of using government-owned land to develop affordable homes for first-time homebuyers was also thought to be helpful among a large majority of renters (79%). Renters also found lowering requirements on down payments for first time homebuyers (67%) and instructing the Bank of Canada to consider lowering interest rates (60%) to be helpful in their homeownership aspirations.

Table 9 — Below are some housing policies that have been proposed or implemented. Thinking about what would improve your personal housing situation, please select how helpful each policy would be.

Immigration and Housing

The issues of immigration and international students and their impact on housing affordability have grabbed headlines recently in Canadian mainstream media. In this study, attitudes towards immigration and housing are related, but confounding, variables that demonstrate notable correlations with housing needs and policies which require a better understanding and nuance before falling into problematic political narratives.

International students in particular have entered the political discussions on housing in recent months due to a dramatic rise in population with this resident status. The rate of study permit holders in Canada had increased rapidly over the past decade, but due to pandemic-induced backlogs, labour shortage demands, and revenue demands of post-secondary institutions, the number of international students in Canada have spiked dramatically over the past couple of years.

Study permits have been used to prop up post-secondary educational institutions in the context of funding cuts and administrative concentration, used by postsecondary institutions as a funding source, and as a precarious immigration pathway where the traditional point system or other avenues are backlogged or inaccessible – all factors which have lead to this issue spilling over into a contentious debate on housing supply and demand.

Overall, 45% of respondents believe restricting immigration to alleviate pressure on the housing supply would be helpful, while 38% believe this would be unhelpful. 39% of respondents say restricting the number of international students to reduce pressure on the rental market would be helpful compared to 36% of respondents who say this would be unhelpful. Combined with the very high perception that foreign investors (48%) are responsible for the housing affordability crisis, despite owning just 2 to 3% of homes in Canada, there is clear contention between public views on international migration and housing affordability which requires deeper investigation.

Chart 16 — Thinking about what would improve your personal housing situation, please select how helpful each policy would be: Restricting Immigration and Restricting International Students

Significantly, renters are more engaged in this issue as newcomers are more likely to participate in the rental market, rather than the homeownership market. Among renters, 54% say restricting immigration would be helpful, while 41% say this would be unhelpful and 6% say this is not applicable. This dynamic certainly differs from homeowners, 40% of whom say restricting immigration would be helpful, 36% say this would be unhelpful, and nearly a quarter (24%) say this is not applicable.

Similarly for renters, 53% say restricting the number of international students would be helpful while 43% say this would be unhelpful. 5% of renters say this is not applicable to them. In contrast to attitudes towards immigration, and with renters on international students, only 29% of homeowners say restrictions would be helpful, compared to 32% who say this would be unhelpful and a statistically significant 40% who say this does not apply to them.

There are also interesting nuances among different age groups. For younger people aged 18 to 29 years old, 54% say restricting immigration would be helpful, compared to 48% for 30 to 49 year olds and 39% of those over 50. Significantly, more than a quarter (26%) of respondents over 50 years old say that this issue is not applicable to them, compared to 8% of 18 to 29 years olds. On restricting international students, 57% of 18 to 29 year olds say this would be helpful, compared to 40% of the middle-aged group, and 30% of those 50 and over. Significantly again, 39% of those 50 and over say this is not applicable to them, compared to 5% of the youngest generation saying this does not apply.

For those that prioritize housing as a concern, 49% say that restricting immigration would be helpful, compared to only 5% of those who say housing is not a concern. Significantly, 40% of those who say housing is not a concern feel that this issue is not applicable. The differences in concern and attitudes towards restricting international students are starker, and one could speculate the direction of discourse focusing on international students, in particular, could be influential. For those that are concerned with housing 44% say that restricting international students would be helpful compared to 17% of those who are not concerned. In contrast, a strongly significant 61% of those that say housing is not a concern, also say that the issue of international students is not applicable.

It is important to understand the dynamics that draw distinctions between international students and immigration writ large among those experiencing different housing affordability challenges when evaluating policies that get government back into housing. The perception of “competition” among more players in an already scarce and unaffordable rental market may result in these rather uncharacteristic attitudes towards immigration among younger people who are struggling with affordability the most. While younger generations are more likely to have positive views of immigration than older generations according to other recent polling, when it comes to housing this study underlines that these perceptions may be less favourable.

Further investigation would be necessary to determine the strength of the housing affordability issue on the overall attitudes towards immigration among young people, that determines the influence of other demographic and socioeconomic factors, to better coordinate housing and immigration policy. Other confounding data points on immigration are the relatively low blame (15%) assigned to immigrants as responsible for the housing crisis, compared to financial actors and governments, as well as the high perception (49%) that foreign investors are responsible (see Chart 12).

Were the government to get back into housing, they must also consider policy changes to immigration, labour, and post-secondary education while also appropriately addressing housing affordability issues today, in addition to favourable policies that build more housing for tomorrow.

Table 10 — Restricting immigration to alleviate pressure on the housing supply

Table 11 — Restricting the number of international students to reduce pressure on the rental market

Conclusion: A Counter-Narrative

The message from Canadians is clear: the federal government is seen as responsible for the housing crisis, and the government must get back into the business of homebuilding to address it. People in the most expensive housing markets feel that leaving the housing crisis for the market to fix is clearly not working. Municipal administrations as well are not really thought of as “gatekeepers” to housing, despite conservative narratives to the contrary.

Federal and provincial governments, alongside the financialization of housing, are held responsible for the ongoing affordability crisis, but this doesn’t mean that voters want less government involvement—instead, there is an appetite for more government intervention in building affordable, non-market housing. Governments are being blamed for the crisis in the perception that they have not been doing enough. Financial actors are held more responsible for the housing affordability crisis than governments, immigrants, and other scapegoats, though blame is still distributed. Young people, low-income households, and those who rent housing are in overwhelming support for measures that get government back into housing, and in particular policies that help to decommodify rental housing.

Administrations that have worked to get government back into housing enjoy stronger support. Governments that have worked to let the market fix the housing crisis are perceived to be responsible for the housing crisis. The federal government, one of the most to blame for the housing crisis while being decades removed from the issue, has the opportunity to be more ambitious on the decommodification of housing to start working towards decades of getting back into housing and ensure that housing truly is a human right for all.

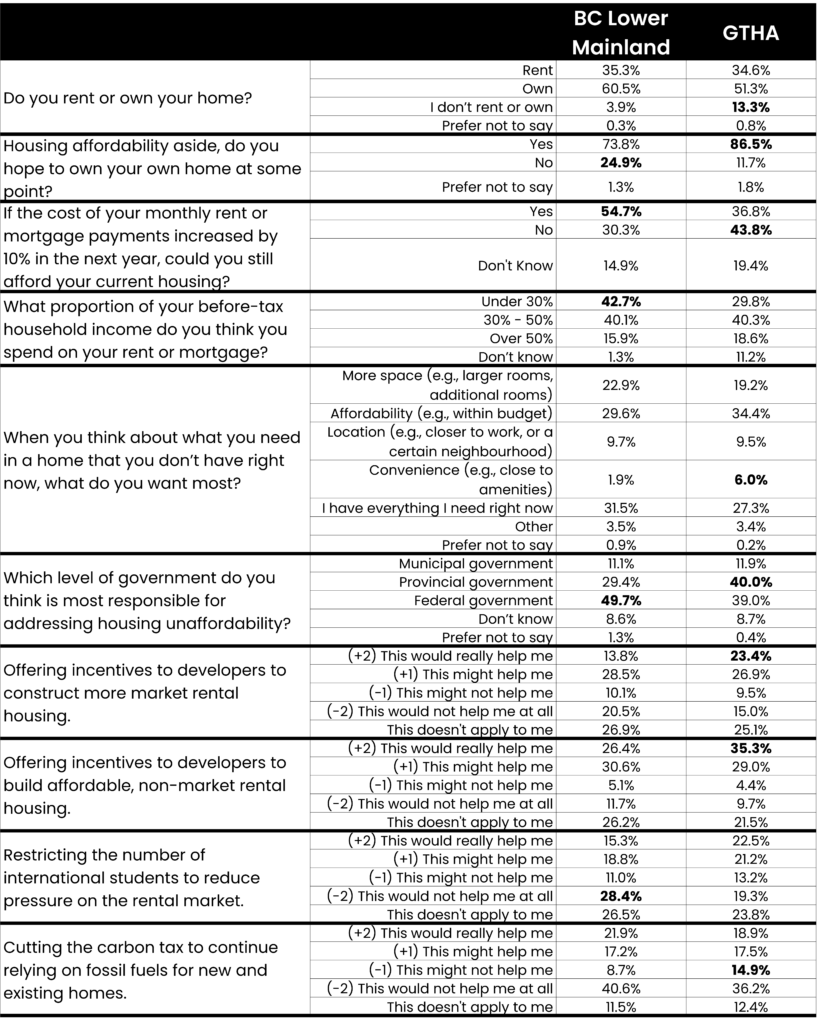

Appendix: Regional Comparison

Select questions demonstrating significant differences of respondents between the BC Lower Mainland and GTHA.

Dreams and Realities on the Home Front: Canadians’ Call for Government Action on Housing Affordability is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0